[ad_1]

This story was printed in partnership with Excessive Nation Information.

In early November, the U.S. Supreme Courtroom agreed to listen to a case introduced by the Navajo Nation that would have far-reaching impacts on tribal water rights within the Colorado River Basin. In its swimsuit, the Navajo Nation argues that the Division of Inside has a duty, grounded in treaty legislation, to guard future entry to water from the Colorado River. A number of states and water districts have filed petitions opposing the tribe, stating that the river is “already absolutely allotted.”

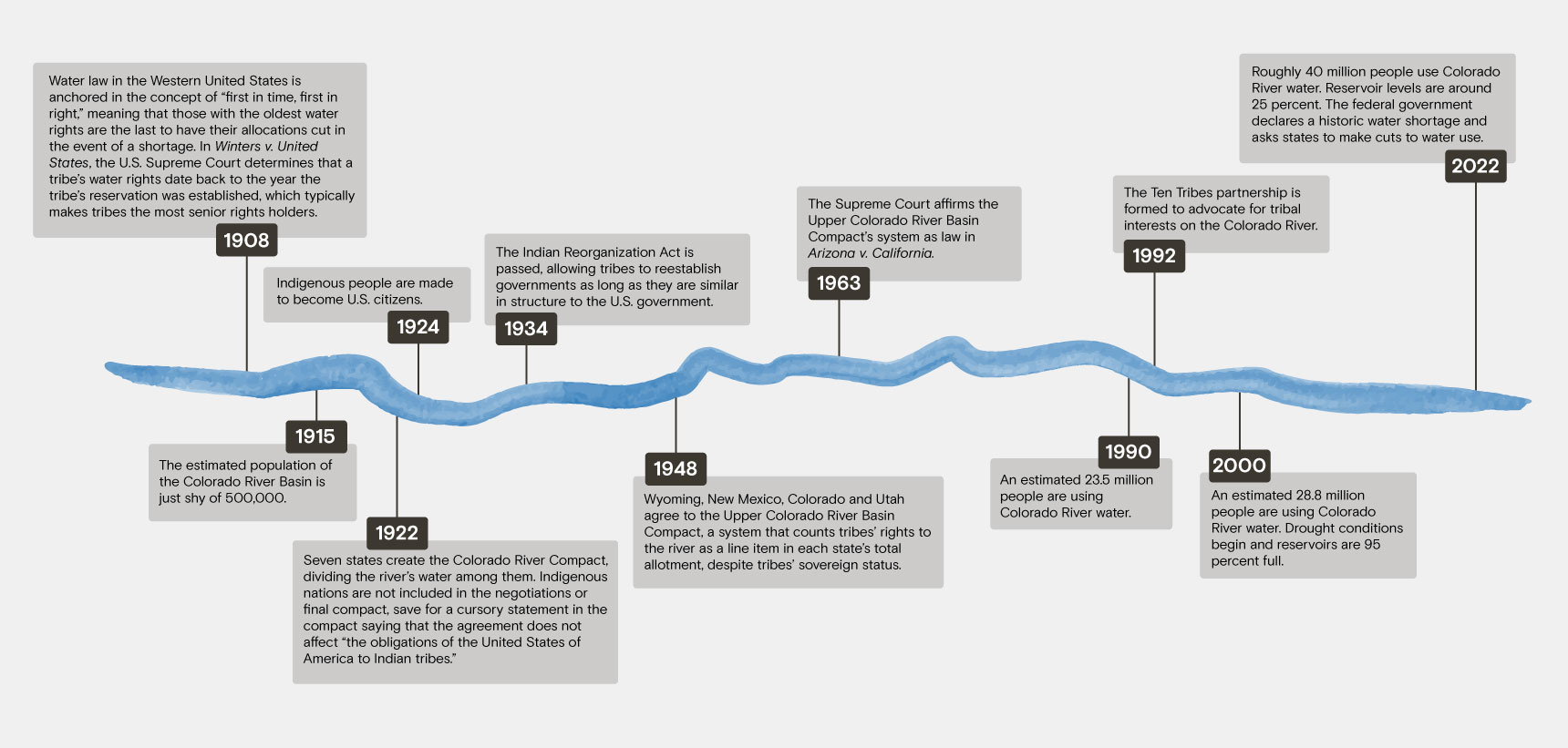

The case highlights a rising stress within the area: As water ranges fall and states face cuts amid a two-decade-long megadrought, tribes are working to make sure their water rights are absolutely acknowledged and accessible.

On common, 15 million acre-feet of water used to circulate by the Colorado River yearly. For scale, one acre-foot of water might provide one to a few households yearly. A century in the past, states reached an settlement to divide that water amongst themselves. However in latest many years, the river has provided nearer to 12 million acre-feet. Scientists say water managers within the basin have to plan for nearer to 9 million acre-feet per 12 months, a 40 p.c lower in a water supply that helps 40 million individuals, on account of local weather change and aridification.

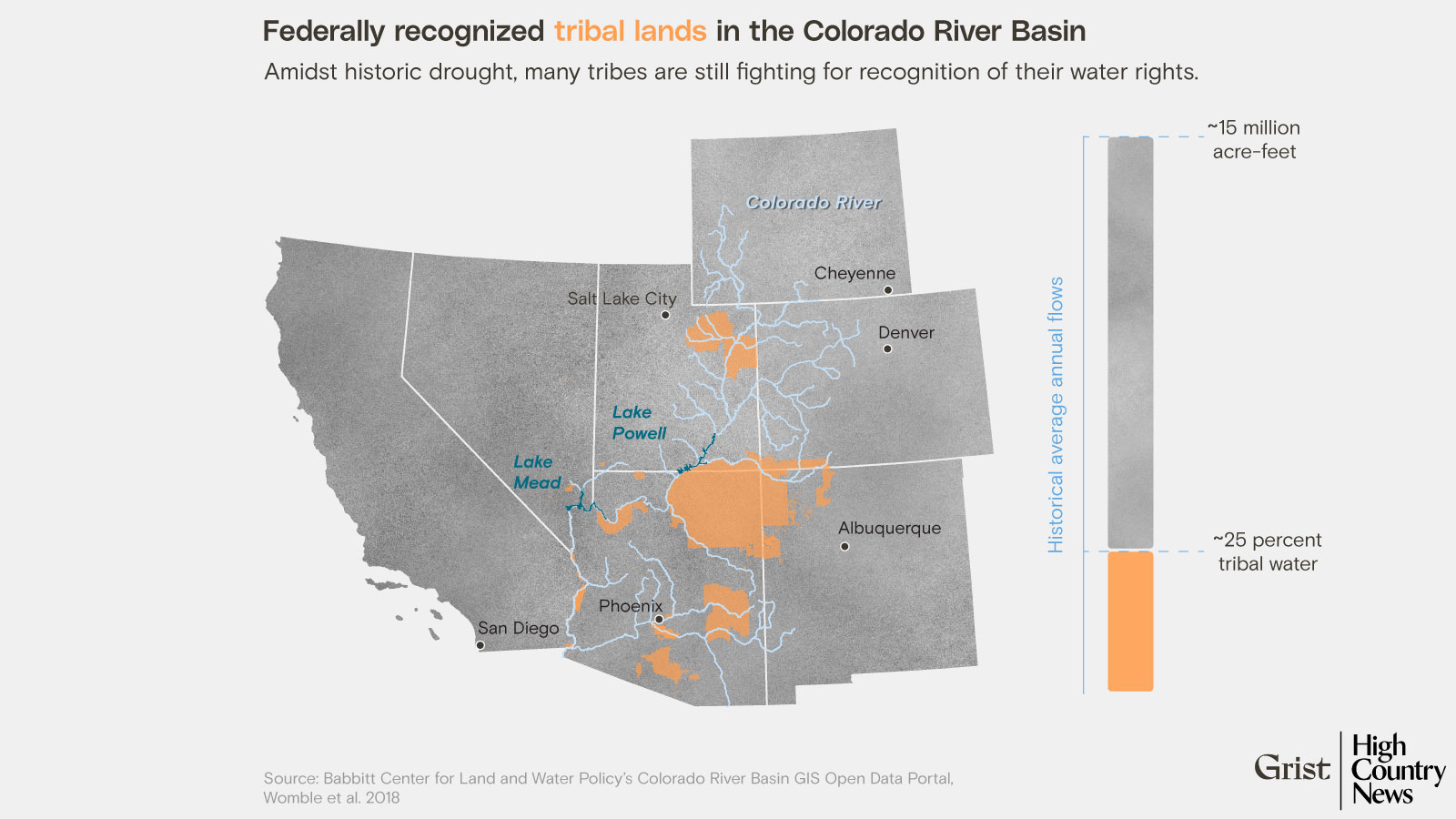

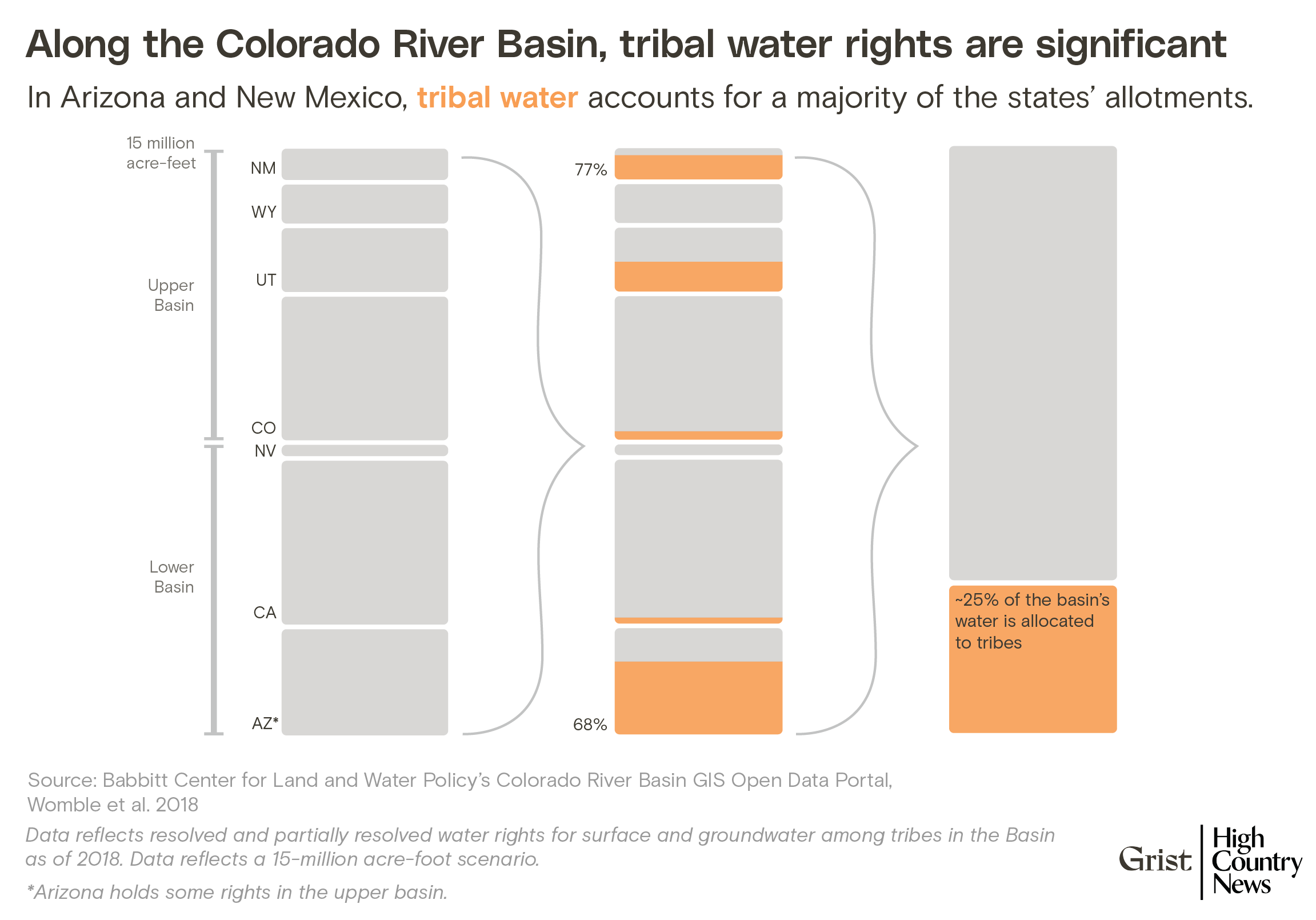

No states have made plans to accommodate this drop. In the meantime, tribal nations are legally entitled to between 3.2 and three.8 million acre-feet of floor and floor water from the Colorado River system.

There are 30 federally acknowledged tribes within the river’s basin, and 12 of them, together with Navajo Nation, nonetheless have at the very least some “unresolved” rights, which means the extent of their rightful claims to water have but to be agreed upon.

In the end, Indigenous nations within the Colorado River Basin may very well be critical energy brokers in essential water negotiations to come back — however they face historic, authorized and sensible obstacles. The Navajo Nation, for instance, has rights to nearly 700,000 acre-feet of water yearly throughout New Mexico and Utah, together with unresolved claims in Arizona. However, due to a scarcity of infrastructure, as much as 40 p.c of Navajo households don’t have working water. For the Navajo Nation and different tribes with allocations within the basin, constructing and enhancing infrastructure means offering residents with entry to a basic human proper: water.

However tribal water use is taken out of state allocations, which means the extra water tribes use, the much less states have. It additionally implies that states have much less incentive to work with tribal leaders or acknowledge pending water rights claims. This battle shouldn’t be new. It has been constructed right into a century of insurance policies which have excluded and divested from Indigenous nations.

Tribes usually maintain senior water rights, which means their allocations are the final to be minimize in a scarcity, and states within the basin are starting to reckon with this reality. A basic shift in how the river is ruled — to a system that acknowledges tribes’ sovereignty and provides them better say — will likely be key to sustainably and equitably distributing water within the years to come back.

Tribes “have to be included in each a kind of conversations and regarded identical to a state or the federal authorities,” Southern Ute Tribal Council Member Lorelei Cloud mentioned on the annual Colorado River District Seminar in September. “You can’t low cost us.”

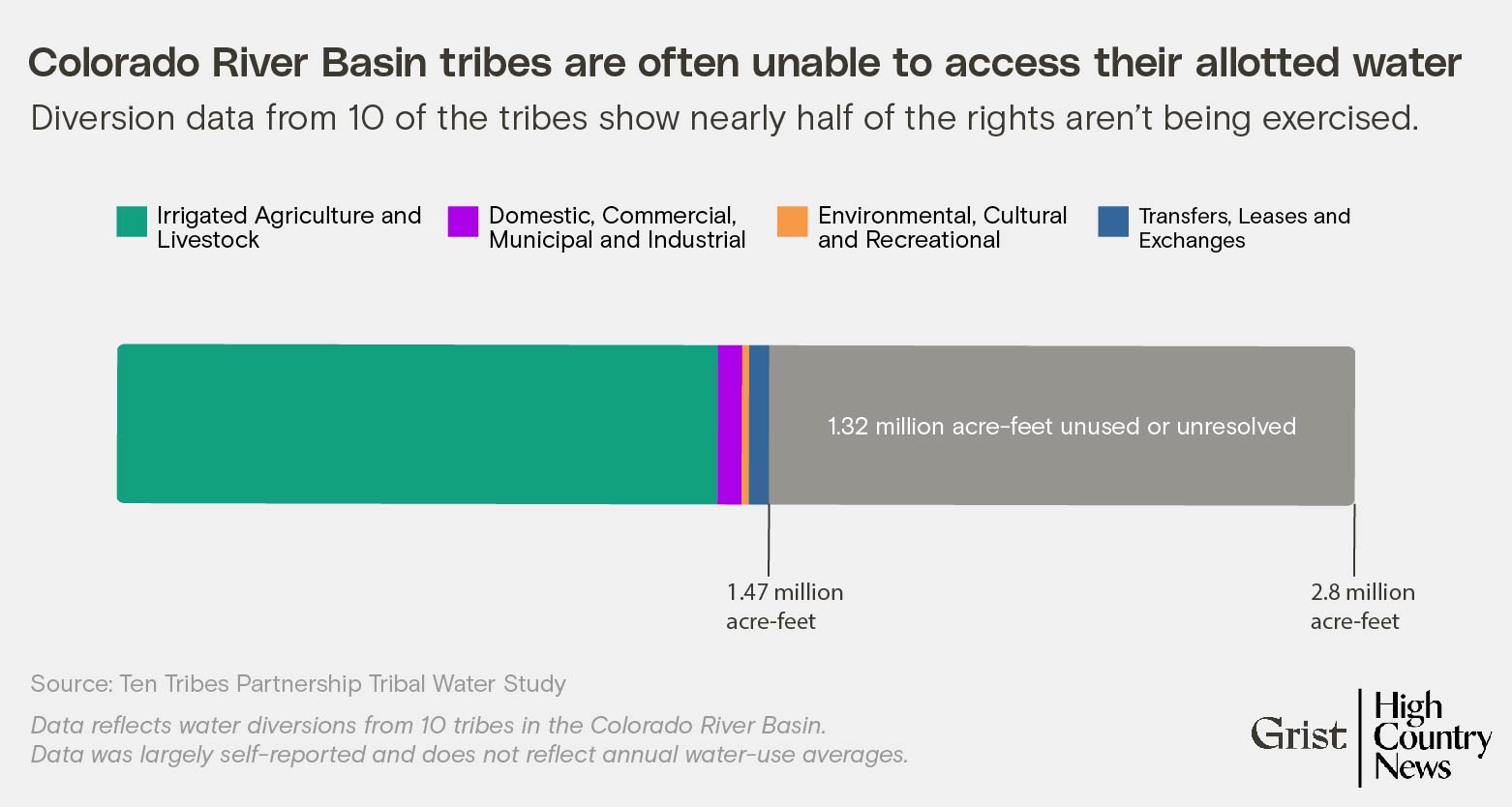

One barrier to equitable distribution is a obtrusive data hole: There is no such thing as a definitive supply of information on water utilization amongst tribes within the Colorado River Basin. Traditionally, federal surveys have ignored tribal water use, and although tribal-led research have begun to fill these gaps, the shortage of information makes planning for a future river with shrinking flows unattainable.

“If you know the way a lot water everybody has or is allotted, then you possibly can provide you with a complete resolution — not simply administration of the river however responses to local weather change,” Heather Tanana (Diné), a professor of legislation on the College of Utah, mentioned in an interview.

In Arizona, for instance, practically 70 p.c of the state’s water allocation belongs to tribes, and practically all of the tribal nations with unresolved water rights within the basin have at the very least some territory within the state. Based on a joint research by tribal nations and the federal authorities, 10 tribes within the basin, which maintain the majority of the acknowledged tribal water rights, are diverting simply over half of what they’re entitled to — most of which is used for agriculture. It’s unclear what water availability would appear to be if these tribes had fundamental infrastructure to get water to their residents, or if all tribes with unresolved rights settled their circumstances.

“My expertise of negotiating water rights settlements in Arizona is that the state of Arizona very a lot approaches them as a zero-sum recreation,” mentioned Jay Weiner, water counsel for the Quechan Indian Tribe and the Tonto Apache Tribe, which has been in settlement negotiations since at the very least 2014. That combative strategy, he mentioned, has persevered no matter governor or political get together. “It’s one thing that appears to be deeply embedded within the cloth of Arizona and the way it approaches Indian water rights settlements.”

In February, the federal authorities introduced $1.7 billion for tribes to make use of for water settlements. Meaning extra tribal residents and communities might have entry to water. It additionally implies that states should work with tribes to plan for the long run and adapt to local weather change.

In some locations, tribes and communities have already been transferring in that course, working collectively to search out place-based options that use the sources and infrastructure at hand. The Pascua Yaqui Tribe and the town of Tucson, Arizona, have an intergovernmental settlement for Tucson to retailer and ship potable water for the tribe, which doesn’t have the infrastructure to take action by itself. Such partnerships will solely change into extra important as drought and aridification proceed to emphasize the area.

“If people work collectively and companion collectively, the chance to unravel the issue, I feel, is enhanced,” mentioned Robyn Interpreter, an lawyer who represents the Pascua Yaqui Tribe and the Yavapai-Apache Nation of their water rights claims.

The federal Navajo-Gallup Water Provide Mission, which is constructing $123 million in infrastructure, is one other promising instance. The aim of the venture is to assemble water vegetation and a system of pipes and pumps that may ship water to the Navajo Nation, the Jicarilla Apache Nation, and the town of Gallup, New Mexico. Crystal Tulley-Cordova, a principal hydrologist for the water administration department of the Navajo Nation Division of Water Sources, mentioned in an interview there’s a new willingness to collaborate, owing to each the severity of the scenario and non-tribal water customers’ realization that they need to work with tribes. “Now there’s a better want to have the ability to work collectively. So I’m inspired by that,” she mentioned.

In the meantime, tribal nations are additionally making progress in securing their entry to water. In Might, the Navajo Utah Water Rights Settlement Act was finalized, granting the Navajo Nation 81,500 acre-feet of water in Utah and licensed $220 million in federal funds for water infrastructure tasks. “Our households rejoice this second in historical past after many years of preventing for the Navajo Utah Water Rights Settlement,” Navajo Nation Council Delegate Charlaine Tso mentioned in a press release on the time. “It’s clear drought circumstances are affecting water ranges throughout the nation. A lot of our elders haul consuming water from miles away whereas we work to get correct water infrastructure tasks accomplished. This settlement permits us to start connecting our water strains to probably the most rural areas.”

Nonetheless, tribes nonetheless don’t have any direct technique of governance over the river, and, as seen within the Navajo water rights case headed to the Supreme Courtroom, states proceed to combat tribal communities looking for entry to water.

Final fall, greater than 20 tribes signed a letter to Inside Secretary Deb Haaland by which they pressed for direct, sustained involvement in re-negotiating the rules that handle the river, that are set to run out in 2026. In Albuquerque, New Mexico, final March, Haaland and Bureau of Reclamation management met with tribal leaders and “dedicated to transparency and inclusivity for the Tribes when work begins on the post-2026 operational guidelines,” in accordance with a spokesperson for the Division of the Inside.

“It’s the job of political creativeness to see what’s doable,” Andrew Curley (Diné), an assistant professor of geography at College of Arizona, mentioned in an interview. “That’s one thing that we collectively, not simply Native nations however led by Native nations, can begin to articulate. What’s a distinct imaginative and prescient of the river than what has been put into legislation and these congressional acts and Supreme Courtroom choices over time?”

[ad_2]

Source link